For years, Gulf capitals have moved from being “luxury consumers” to “owners and shapers” of the global fashion industry. Their role is no longer limited to buying clothes; it now extends to owning the companies that produce them and control their narratives.

Gulf investment in fashion has become an economic force. Earlier this year, Abu Dhabi’s Multiply Group — an Emirati investment fund — acquired 68% of Spain’s Tendam Group in a deal worth nearly €1 billion. In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), the kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund, bought 40% of Selfridges in the UK. Long before that, Qatar purchased Harrods, and Mayhoola — a Qatari fund — became the owner of Valentino and Balmain. Even companies not fully acquired have entered partnerships with Gulf players—Inditex, for example, handed over its Russia operations to an Emirati firm.

These moves aren’t random. In Saudi Arabia, they fall under Vision 2030’s drive to reduce reliance on oil and diversify the economy. In the wider Gulf, they are part of a broader push to invest in “soft power” sectors like sports, entertainment, and fashion. But here’s the question someone raised in a recent discussion: Is the Gulf only buying value, or creating it? Is it still just a financier, or a true cultural producer?

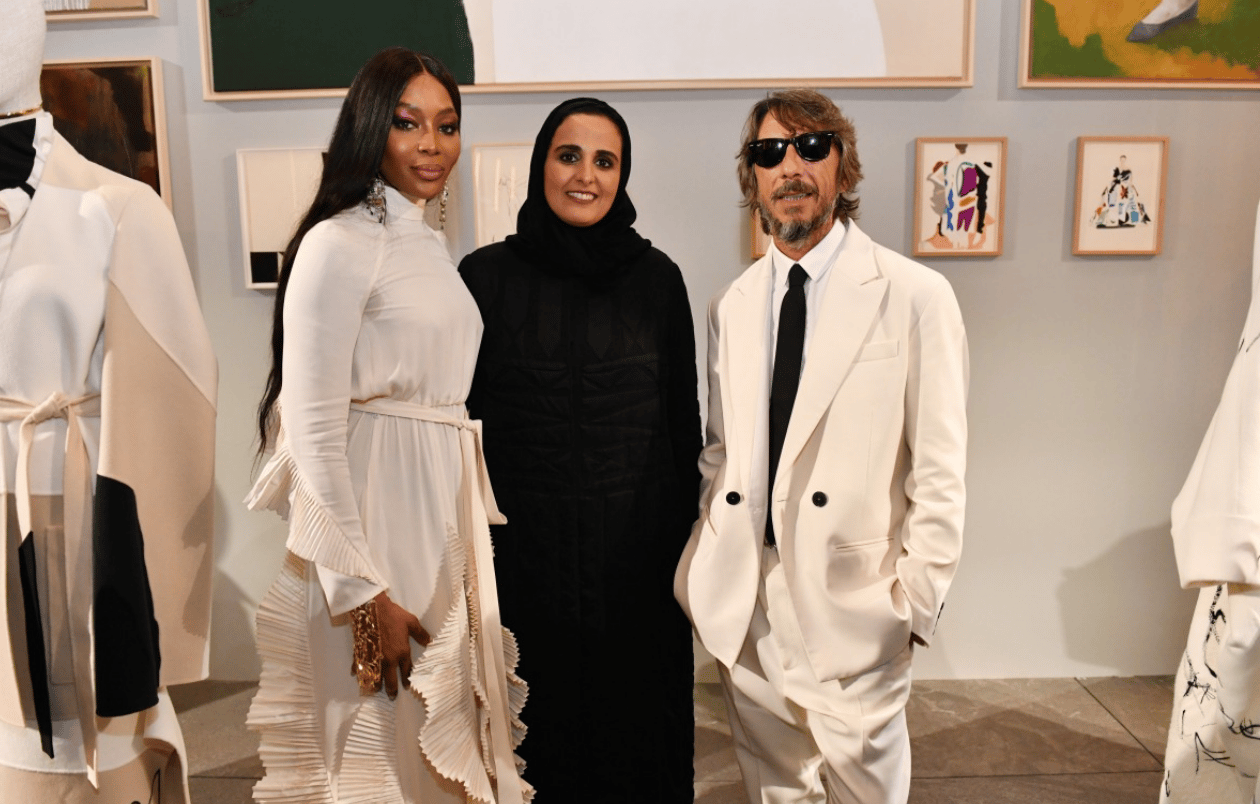

That question matters. Because reality is more interesting than the stereotype. Today, the Gulf runs on two parallel tracks: on one side, it owns established global brands that strengthen its international footprint; on the other, it is building a local fashion infrastructure from scratch—training designers, developing specialized education, and planting seeds for homegrown labels that could compete globally in the future. It’s a calculated balance.

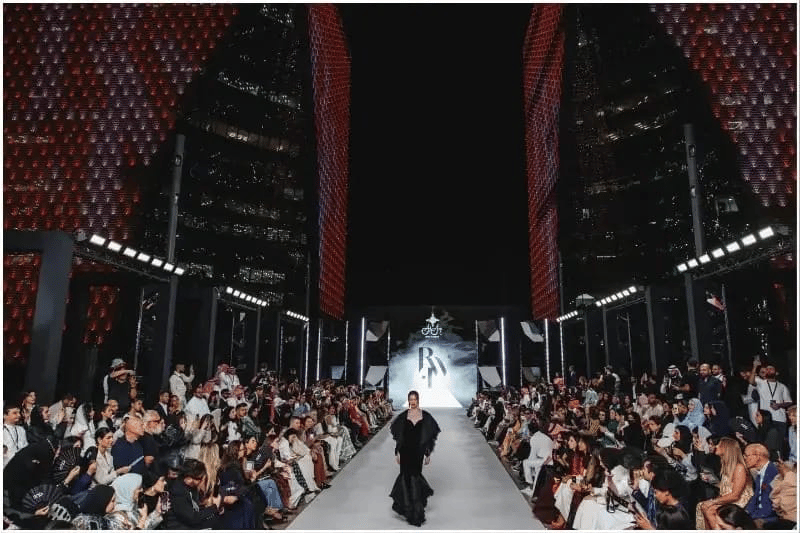

A glimpse of Riyadh Fashion Week

Cultural representation inside these global houses, however, is still thin. The visibility of Gulf narratives does not match the scale of Gulf money. Consumers here have yet to demand seeing themselves reflected in the brands they bankroll. Or maybe they don’t fully realize how much influence they already have.

Last year, a media platform reported that European brands still find the Gulf market “hard to read,” treating culture as a barrier. That excuse no longer holds. With tourism surging, especially in Saudi Arabia, and with booming markets in Qatar and the UAE, brands now have every reason to understand this audience deeply. No more hiding behind stereotypes.

When we look beyond transactions into culture, the issue isn’t only weak representation abroad. It’s also our own long detachment from identity. Since the late 1970s oil boom, whole generations have been educated in systems that didn’t reflect their own heritage. We kept the slogans of identity, but not the content.

A Saudi academic who studied fashion design in the early 2000s told me she and her classmates were asked to research Egyptian or Greek civilizations but never their own. Local culture wasn’t seen as a legitimate source of study or inspiration. Now, as faculty, she says she’s stunned by how much her students uncover about Saudi visual culture—rich material she and her peers once ignored

This gap in the curriculum produced a gap in self-perception. As historian linguist Dr. Abdulmajid Al-Mudarraa notes, “Official attention today is rewriting our heritage after it had been hijacked and written their way.” We grew up with a one-note image of the Arabian Peninsula—desert, tents, camels. That image isn’t wrong, and we take pride in it, but it’s only part of the story, not the whole story.

This land birthed ancient civilizations like Al-Maqr, Kindah, and the Nabataeans long before Christ, and today it’s building NEOM. Its visual and cultural diversity rivals any past civilization—but we weren’t encouraged to discover it.

Ask a local designer today about Coco Chanel and they’ll narrate her biography in detail. Ask about Dior’s Bar Jacket and they’ll dissect its construction. Mention Tahera Al-Subaie—the first to document Saudi fashion in the 1980s—and many will draw a blank. Bring up the “Mubqar Al-Taifi” — a traditional Saudi garment from Taif known for its architectural-level construction and intricate details, even though its complexity matches French couture — and it’s often treated as just another “traditional piece.”

This detachment also fuels a shallow debate about “identity” in design. Some say you don’t need to reference heritage in every piece. Fair—but that view often reflects a narrow idea of identity reduced to Najdi patterns or Al-Asiri motifs slapped on sleeves. Real identity means diving into ancestral crafts, studying the arts born in your environment, understanding their functional and aesthetic logic, and then reinventing them with a contemporary vision.

In today’s fashion industry, true differentiation is rare. Identity might be the last authentic way to create something genuinely new.

This isn’t blame. It’s a diagnosis of a cultural vacuum left open for decades and filled by others’ stories—stories we’ve learned to tell better than our own.

But the picture is changing fast. Saudi Arabia’s geographic and cultural diversity—from the ancient kingdoms of Dadan to the futuristic city of NEOM—is an untapped treasure for designers. If you’re a local designer, the moment is yours. Don’t return from your studies armed only with imported techniques; come back with a vision rooted in your environment and speaking your own language to the world — the same way French couture rooted itself in its own crafts.

The eyes of the world are already on us. The future won’t be dictated to us—we will write it ourselves. But only if we know who we are and what we want to say.