In Saudi traditional dress, you often see the repetition of intricate geometric motifs and interlaced vegetal patterns. They appear on robes, in embroidery, at sleeve edges, or woven directly into the fabric. Each time these designs return to the spotlight, curiosity renews: why these specific motifs? Were they simply aesthetic choices echoing nature, or do they have deeper roots in the region’s visual and cultural history?

Looking at the history of Islamic art, it’s clear these elements were not mere decoration but a visual language with intellectual and spiritual meanings. Because Islam discourages the depiction of living beings, artists developed other modes of expression, relying on mathematics and geometry to build a complete visual system.

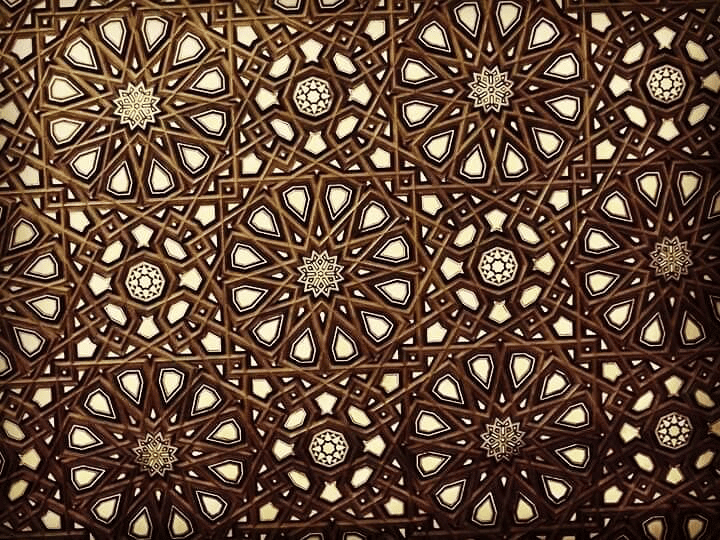

The Star Plate

One of the best-known configurations is the “star pattern,” which divides the circle into geometric units that interweave to form multi-pointed stars. These patterns are executed with mathematical precision, carefully calculated angles and measures, giving the eye a sense of expansion, harmony, and discipline. This is no accident; it extends a philosophical view that finds beauty in repetition and in the order of detail.

Alongside geometry, nature also played a role—but in a different way. Islamic vegetal motifs do not imitate a flower as it is; they rebuild it ideally, transforming branches and petals into balanced, symmetrical models that retell life as an organized movement, not chaos.

Art historians point out that the Muslim artist expressed his spiritual vision through three essential tools: geometry, rhythm, and light. Colors were also central; their richness and luminosity reflected a desire to evoke the atmosphere of paradise as described in the Qur’an—a world saturated with beauty, light, and life.

Naturally, this art also seeped into traditional dress. Patterns embroidered with gold or silver threads are an extension of the same language, finding in fabric another medium to assert order, beauty, and symbolism.

The American designer Charles Eames once wrote:

“Design depends largely on constraints. A great deal of creativity is born from the discipline of limits.”

Islamic art is a perfect example. It emerged from strict boundaries but didn’t stop there; it transcended them and created an art based on precision, discipline, and contemplation.

Constraints are often seen, especially in creative fields, as obstacles that limit freedom or as rigid molds that shackle imagination. But the Islamic experience in art suggests a different view: constraints are not the end of the road but its beginning. When an artist is forbidden from using ready-made tools—like depicting faces or bodies—he is forced to search for new ones. The constraint becomes an open question: how do I say something without saying everything? How do I express without representing?

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri on Windows

This challenge produced the language of Islamic art—a language built not on imitation but on suggestion. It doesn’t show meaning directly but hints at it. That gave Islamic art astonishing symbolic power, because it didn’t merely reproduce reality but sought to interpret, deconstruct, and rebuild it in ways that aligned with the community’s religious and cultural worldview.

This experience teaches us that the absence of certain tools does not necessarily mean the absence of possibility. On the contrary, when some doors close, a wider door to imagination can open. The artist begins to see things differently—more precisely, more deeply. Islamic art was never a “deficient” art as some Western critics once portrayed it; it was a coherent art with its own inner logic, its own tools, and a distinctive vision of the world.

This meaning is also clear in the work of fashion designer Peter Mulier, creative director of Alaïa, who in 2024 presented one of his most acclaimed collections made entirely from a single material: merino wool. This was not a lack of resources but a conscious creative decision, known in fashion circles as “the hungry designer syndrome”—a concept where a designer deliberately limits himself to one material or rule to test the farthest reach of his creativity.

It’s exactly what Islamic art did in a moment of restriction: turning boundaries into a driver of invention, and limitation into a method with its own language, logic, and beauty.

This article is supported by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra) and the Cultural Development Fund as part of the #Ithra_Arabic_Content_Initiative.